Kampala, Uganda: The Case of Pit Latrines for Sanitation

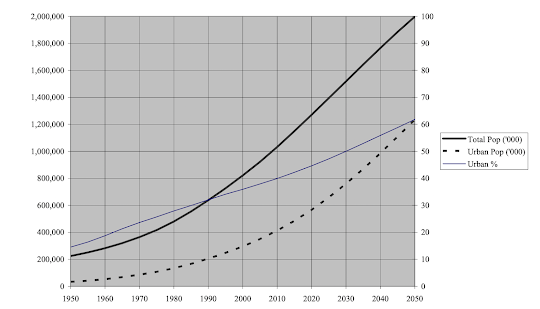

Meeting the SDG 6 mentioned in my previous blog post, may be a challenge for countries in Africa.

Challenges faced by Kampala, the capital city of Uganda will be the focus of this blogpost. Water supply, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions in these environments are often unimproved due to regulation issues, low budgets and lack of capacity. Therefore, I will aim to explain the how pit latrines work, then depict the challenges present with them and finally propose ideas and suggestions on how to combat the challenges present.

Approximately 90% of households in Kampala use on-site sanitation facilities and primarily pit latrines. However, Kampala is not alone as many low-income countries chose pit latrines as their most common disposal of faecal waste in aims to reach targets of SDG 6. Graham and Polizzotto suggest that 1.77 billion people use pit latrines as a primary means of sanitation.

How do pit latrines work?

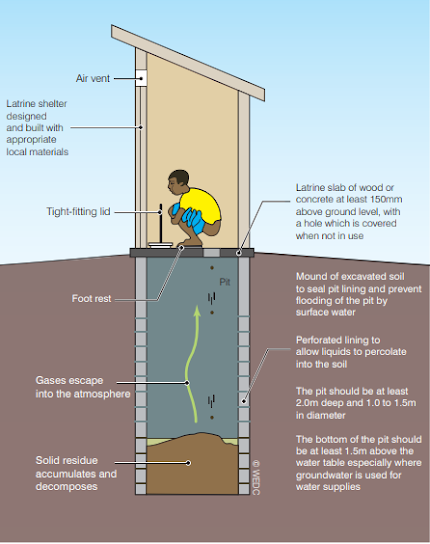

Excreta falls into a hole in the ground. Then, through bacterial, fungal and other organisms, the faeces is decomposed in aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Pathogens that otherwise would remain on the land will be destroyed within the pit. Pit latrines are often popular in low-income regions as they can be developed by users, are cheap and materials required for building pit latrines are minimal. Figure 1 shows a simple pit latrine:

What makes a pit latrine improved? Challenges involved:

The design, construction and structural conditions are important for the appropriate function of pit latrines. The materials that are recommended and up to standard is shown in the 5th column in figure 2:

Figure 2. Design and construction materials of pit latrine structures.

a

n value for vent pipe = 30.

The pit latrines in Kampala used mostly strong and durable materials and met the standards recommended. Therefore, it could be suggested that the pit latrines in Kampala are ‘improved’. However, cracks were present in 39% of pit latrines and 40% showed signs of water from rainfall entering the latrines indicating that faecal matter could leach into water systems and contaminate water systems which could potentially lead to disease.

5% of pit latrines have manholes constructed. Manholes make emptying of pit latrines easier but only 5% of pit latrines have them. Despite up to standard materials being used for the construction of pit latrines, if cleanliness and emptying of pit latrines are not maintained to a good standard, the potential of leaching faecal matter into water systems increases. Evidence to suggest the importance of cleanliness is provided by logistic regression whereby the level of cleanliness was the strongest predictor (𝛽=97.6) of odour. Dirty pit latrines are 97.6% more likely to smell badly compared to a clean one. Strong odours may prevent one from using a pit latrine or make it uncomfortable to use, hindering sanitation effects of reaching SDG 6.

Although most of the latrines in the study were labelled as ‘improved’ there are still issues with their construction (lack of manholes) and usage (cleanliness). Also, only 10% of the latrines included ramps making it difficult or impossible for those with disabilities to use them and thereby excluding those who are most marginalised. If everyone cannot have access to a sanitary facility, then they are unable to meet their basic needs which hinder developments in reaching SDG 6. The performance of pit latrines in Kampala was also insufficient. 7 of every 10 pit latrines were full or overflowing thereby leading to risks to health as faeces is not isolated properly. Poor design and construction can also lead to collapse before the pit is full. The lack of privacy is also a call for concern, especially for women as latrines are located outside the home.

A different perspective on the struggle for improved sanitation facilities for all could be due to regulations surrounding the management of on-site sanitation facilities like pit latrines. Although legal frameworks are present in Uganda the enforcement of these frameworks has been limited. Furthermore, a huge data gap remains which affects monitoring the effectiveness of sanitation systems in place within areas like Kampala.

Some of these issues can be challenging to solve, especially given the limited funding. Pit latrines should be developed with higher walls for privacy and manholes for cleanliness. Sewers are not feasible for much of the world's poor yet and therefore focus should be on maintaining pit latrines to a high standard as the priority for the near future. Only then can we collectively get closer to reaching SDG 6.

Great details of pit latrines in this post but can you provide some indication of whether the situation in Kampala is representative of or consistent with a situation in African cities more widely? The subject of a future post?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment. That is a great idea! I think showing whether a solution works or showcasing situations should be applied to the wider context of Africa - I think it's especially important to see if the situation in Kampala is similar to other locations across Africa so that we can see if one solution is likely to work in different locations. I will make sure to feed this into future blog posts. Thanks!

Delete