Population growth - the case of Kisumu Town

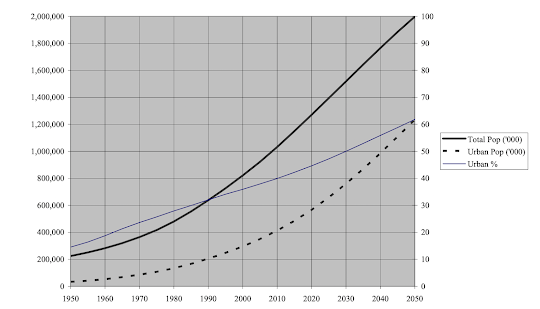

Drangert et al suggest a hypothetical relationship between population increase and infrastructure to explore how infrastructure behaves through different demographic stages as shown in Figure 1.

At A-B there is slow infrastructure development as there is little population growth and therefore demand of sanitation services could be met by own- key arrangements which are activities that are ‘managed and controlled by local communities’. There is little incentive for governments to invest in sanitation infrastructures at this stage. However, the lack of investment is an issue at C-D where often there is no or deteriorating infrastructure at a point where population rapidly increases. Here, existing infrastructure is left in a poor condition as it is strained by the population growth. At this stage, the best outcome could be to focus on own-key arrangements that do not require help from the state but are often not supported in the formal sector. In the following paragraphs, the case of Kisumu, a port city in Kenya, will aid as an example of how ‘going small’ or using own-key arrangements is beneficial during this time period. Finally, at E-F, the rapid population increase is likely to slow down and governments will have enough money to invest in sanitation infrastructures. Here turn-key and own-key arrangements can be adopted.

Therefore, we need innovative solutions which can enable us to manage the sanitation infrastructures that allow for safe water and sanitation for the people in Africa. One solution which is suggested by Drangert is harnessing the skills, knowledge, and materials of local people. Local people have been living there for decades so they will most likely know what's best. We can see this approach in the following example of Kisumu:

We will examine the hypothesis that we should go small in cases where the population is expanding rapidly.

A commercial well was built by an individual to serve the needs of his community in Migosi (in Kisumu), for when the communal taps ran dry and were able to yield 600 litres per hour. Much of the local community prefers this method for collecting water as they’d have to wait much longer at neighbouring wells because of water vendors who fill lots of containers at a time. Therefore, the owner of the well honed his local knowledge (of identifying the long wait times of neighbouring wells) and used his skills to install an electric pump within his house and breakthrough boulders and rocks to get to the water table. Through local knowledge and skills, people can work as a community to provide water in a safe way instead of inflated prices by large corporations that lots of individuals are unable to afford. The well was a success and influenced other households to build their own wells nearby. Developing wells in this way allows for full control over the supply and management.

However, the groundwater in Kisumu has a threat of degradation. So for the case of Kisumu, they should incorporate other specialist help alongside local knowledge and solutions like the one mentioned above. Specialist help can aid in identifying and mapping where degradation is at its worst so that the locals don’t pump water from there for a certain period of time or develop solutions for specific sites first so as to not waste resources. Groundwater in Kisumu was found to be contaminated due to water drawing techniques (from buckets and ropes which weren’t hygienic and surface runoff and objects falling into the well). The contamination of water sources was noted by locals and so they were able to identify the problem but may need some specialist help to solve it. At the stage where population growth is rapid and there is not enough governmental support to aid specialists, NGOs can step forward to help in identifying degradation within Kisumu so that the own-key arrangements are more effective.

To summarise, local knowledge and going small is crucial to prevent degradation of water sources further and ensure that water is safe for the residents of Kisumu. But, we should note that each area in Africa could be different, both in the problems of sanitation they face but also the solutions they require - some places may need more specialist knowledge and others local knowledge. The case for Kisumu proved that ‘going small’ was the correct solution but could aid in some specialist help to ensure the sustainability of these water sources.

Comments

Post a Comment